What is on the inside of an art object? To answer that question, art experts can use an X-ray machine. Some museums own one for inspecting their objects. They use the machine to see whether an object has woodworm, for example, and to what extent. But such X-rays have drawbacks. You see everything on top of each other with no depth, so you can never really make a cross-section of the object. A CT scanner can do that but not many museums can afford one. Bossema and her supervisor Joost Batenburg wondered: can we make better use of what we already have?

X-ray machine becomes aspiring CT scanner

A CT scanner is actually an X-ray scanner that captures the object from all angles. So you take hundreds or thousands of X-rays in a row. You then use a reconstruction algorithm to use those photos to create a 3D model of the object, which you can digitally slice in different directions. With a professional CT scanner, as in a hospital, the knowledge of the exact position of all parts is automated. Bossema has now developed an algorithm to gather that knowledge after the scan has been made. Thus, a simple X-ray scanner becomes an aspiring CT scanner.

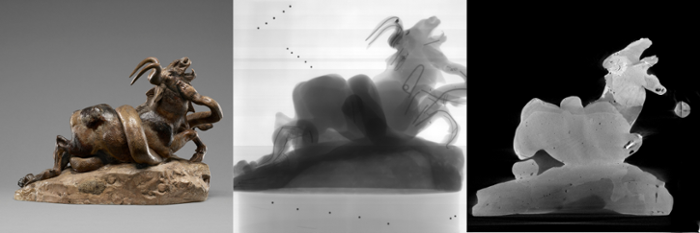

Metal balls as placeholders

We've had the X-ray scanner and the algorithm. Those small metal balls, what about them? Bossema: ‘To make a CT scan, you need to be able to move the X-ray machine around the object. When you do that, you have to know exactly where everything was during the scan. Where is the source in relation to the turntable? How many degrees are we rotated between two X-rays? Where is the detector located? All these places you need to know very precisely. That's why we put small metal balls next to the object.’ These balls have a very high density and become thick black dots on the X-ray photo. ‘We look for black dots on those X-rays, which naturally move when you turn the object. With these reference points, you can calculate how much the object has been rotated. If you know that for all the photos, you can construct a 3D image of the object.’